Biomanufacturing Scale Up

Reading Writing And Editing Dna

Ending The Waiting Game: How Ansa Biotechnologies Guarantees are Turning DNA Synthesis Into A Predictable Industry

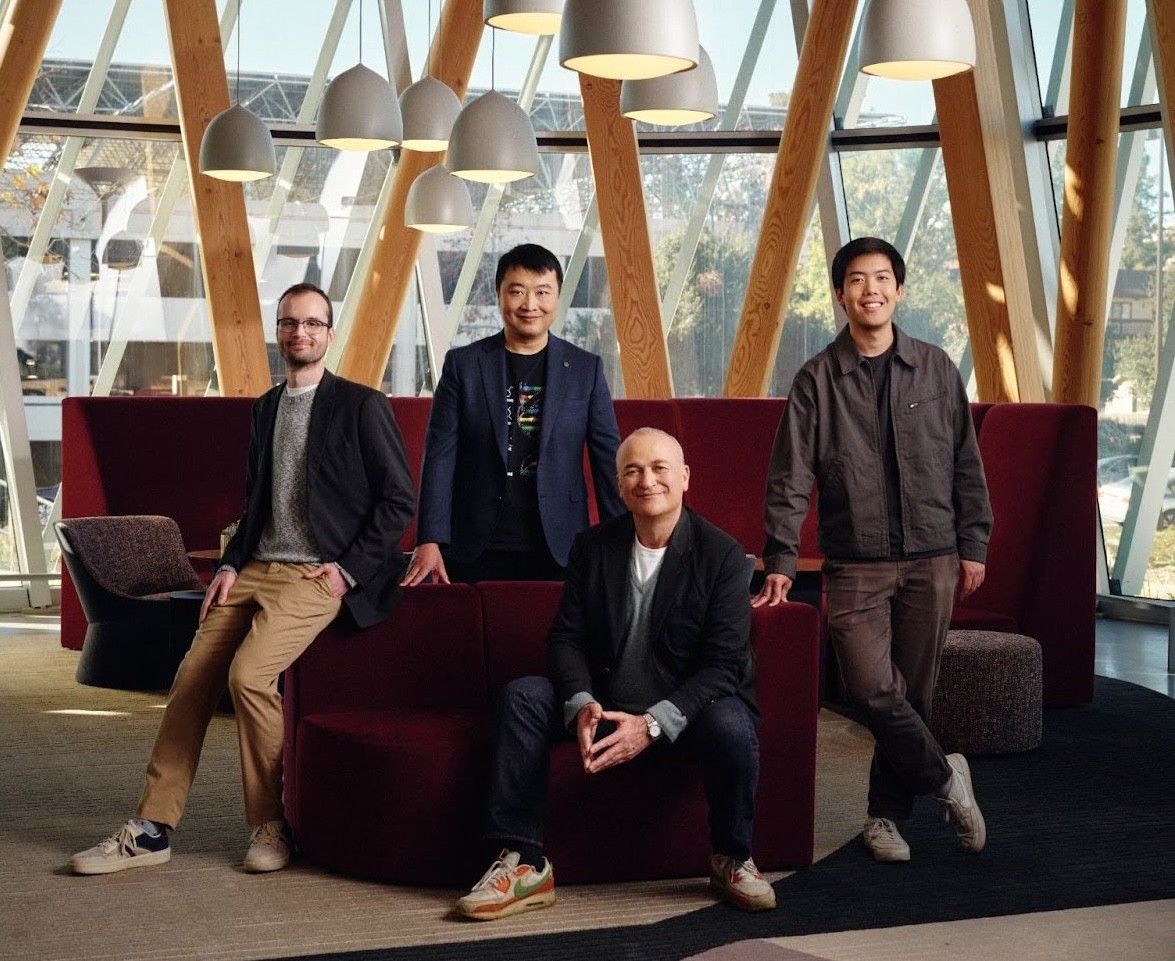

Jason Gammack speaking at SynBioBeta 2025 in San Jose.

When Jason T. Gammack talks about DNA synthesis, he does not start with base chemistry or instrument design. He starts with broken promises. For decades, synthetic biology teams have designed pathways in hours, then waited weeks or months for gene fragments that arrived late, arrived wrong, or never arrived at all. “Legacy vendors often fail to deliver what scientists actually order when they need it,” he said. “In some cases, the DNA never arrived at all.”

Fresh off a 54.4 million dollar Series B financing round, Gammack, CEO of Ansa Biotechnologies, argues that this reliability gap is now one of the biggest constraints on the field. “Our first year of commercialization proved what we already believed, reliability wins,” he said. “When you can deliver 50 kb of clonal DNA in 24 days or less, and you are bold enough to guarantee entire orders, you do not just compete, you reset the rules.”

Ansa’s answer is as much a business model shift as a technical one. The company introduced the Ansa On-Time Guarantee, if a customer’s complete order does not ship on time, the DNA is free. Service level agreements are standard for many reagents, but unprecedented for custom genes, where missed deadlines have long been treated as an unavoidable cost of doing science.

“Customers should have the same confidence in placing orders for synthetic DNA that they do for any other reagent,” Gammack said. “If we say we can make your construct, we will deliver it on time, every time, or your entire order is free.”

The company’s origins reflect the same frustrations many SynBioBeta readers have faced. Co-founders Dan Arlow and Sebastian Palluk were graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley, designing synthetic pathways in silico in hours while waiting months for the DNA to test them. That repeated failure convinced them to pivot and invent a new way to synthesize DNA, work that later formed the basis of Ansa’s enzymatic platform. Gammack joined as the first commercial CEO to turn that technical breakthrough into a business. “I came to Ansa because this technology was not incremental. It is the future of how genomes will be written,” he said.

Traditional phosphoramidite chemistry degrades strand quality as length increases, which is why chemically synthesized assembled genes have historically topped out at around a few kilobases, and anything beyond roughly 10 kb has required fragment stitching and extensive troubleshooting. Ansa’s platform uses a fully enzymatic process based on terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and nucleotide conjugates in aqueous conditions. By avoiding harsh chemicals and building one base at a time, the company can produce long strands without the drop-off that limits chemical synthesis.

In October, Ansa announced a 50 kb clonal DNA product, the longest sequence-perfect synthetic DNA commercially available. Every construct is verified with long-read sequencing and proprietary informatics before shipment. “The platform produces the longest, cleanest, most accurate DNA ever printed, enabling sequences once considered unsynthesizable,” Gammack said. “With our unique technology, Ansa has transformed DNA synthesis from a trial-and-error approach into a predictable manufacturing process.”

The ability to deliver long, sequence-perfect DNA on predictable timelines changes how customers design experiments. Whole pathways and multi-gene systems can be ordered as single clonal constructs instead of stitched fragments, and early customers are using Ansa’s long constructs in synthetic genomics, metabolic engineering, agriculture, and cell and gene therapy. Over the next decade, Gammack expects a larger structural shift. “The big trend is the shift from buying genes to buying genomes,” he said. “Multi-construct assemblies and large-scale libraries will become much more common. The shift from buying genes to buying genomes, combined with AI-driven design and real-time enzymatic printing, means moving from concept to DNA in days.” The company reports a greater than 97 percent fulfillment rate for long, complex constructs, a critical signal for pharma, industrial biotech, and government customers.

Raising a large growth round in 2025 has been difficult for many platform companies. Ansa’s 54.4 million dollar Series B, led by Cerberus Ventures with participation from both existing and new investors, brings total funding to more than 134 million dollars and is intended to scale commercial operations. For Gammack, the round is validation of execution. “Our Series A validated the technology. This Series B is about scaling and capturing the market,” he said. “Investors fund inevitability, not possibility. In down markets, clarity and execution are the strongest currency.”

With the Series B closed, Ansa is expanding its U.S. manufacturing capacity to 24/7 operations and investing in new design-to-test tools that integrate sequence design, manufacturability assessment, and ordering into a single workflow. “Scaling throughput and improving cost efficiency are our top priorities for the next 12 months,” Gammack said. “We are broadening the e-commerce platform and deepening relationships with strategic customers so that ordering a 40 or 50 kb construct feels as routine as ordering a 1 kb gene used to be.”

As more companies move from reading genomes to writing them, the ability to reliably print long, complex DNA on predictable schedules becomes a strategic capability. “The genome writing era is arriving faster than most people think,” Gammack said. “Our job is to remove uncertainty from the path between an idea and the DNA that encodes it. Once you can move from concept to DNA in days, the only real limit left is imagination.”

Portrait of Jason Gammack. Photo via Andrew Noble.