Food Agriculture

Biomanufacturing Scale Up

Bioeconomy Policy

New PhD Training Programme Aims to Bridge the Biomanufacturing Scale-Up Gap in the UK

A collaborative effort between three universities and industry seeks to equip graduates with essential skills for scaling biomanufacturing processes.

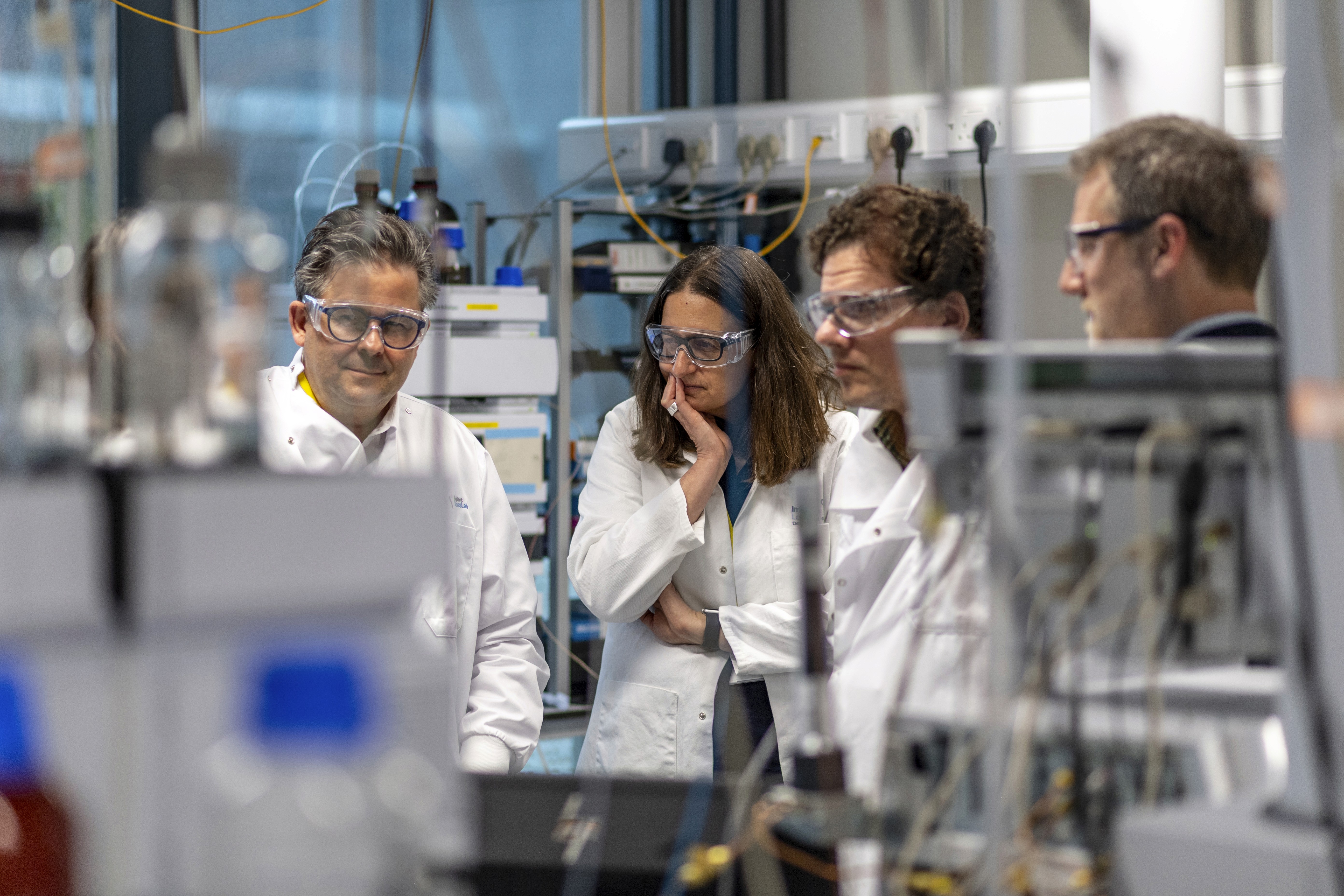

The science of engineering biology enables the utilization of microorganisms and mammalian cells to create chemicals, food ingredients, and materials in a sustainable manner, as well as to innovate entirely new products. However, transitioning these developments from the lab to industrial production presents significant challenges.

To address this issue, a new PhD training programme spearheaded by Imperial and BASF aims to equip students with the necessary knowledge and skills to facilitate this scaling process.

“In the lab we might be working with one litre or ten litres, whereas industry works with thousands of litres, and there is often a gap in both understanding and training when we have to move from one to the other,” explains Dr Sonja Billerbeck of the Department of Bioengineering, who co-directs the programme. “We are trying to bridge that gap, so that graduates learn what they need to know in order to use these processes at a really large scale.”

Engineering biology is paving the way for sustainable production of food supplements and ingredients, such as dairy proteins, fats, and meats. It also provides innovative substances like fabric dyes that do not depend on petrochemicals, as well as antimicrobial and antifungal compounds for biopesticides.

“At BASF, we see biotechnology as a key driver for a more sustainable chemical industry. Its success, however, depends on scalability and cost competitiveness. That’s why we’re excited to join this PhD training programme in biomanufacturing, equipping future scientists with the skills and mindset to turn ideas into viable industrial solutions,” states Dr Averina Nicolae, Open Innovation Manager at BASF. “We offer students real-world challenges, a holistic view of technical, economic, and regulatory factors, and the inspiration to become innovators.”

The programme, named the Sustainable Centre for AI-Leveraged Efficiency in Industrial Biotechnology (SCALE-IB), unites the strengths of Imperial, University College London (UCL), and Aberystwyth University. It is funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), with contributions from BASF, Bühler, and various companies interested in engineering biology.

"The commitment of BBSRC to support in-depth knowledge building and excellence in engineering biology for the food system reflects the need for innovation in an economically critical sector,” remarks Dr Ian Robert, Bühler’s Chief Technical Officer.

These partnering companies, ranging from multinationals to startups, will provide expertise and resources for the training programme and offer students placements for hands-on biomanufacturing experience. This includes sourcing and managing the feedstock for cells or microorganisms, optimizing fermenters and other processes for growth, and extracting and refining the final products.

“We have partners along this whole biomanufacturing chain, so we can train students in every aspect of that process,” Dr Billerbeck notes. “In this way they can develop the systems thinking they need, so that when they engineer their cells and design their processes, they already know what they are aiming for in terms of the product, how it will be produced and how it will be regulated.”

“Scaling innovations from the lab to industrial reality is a complex and challenging process,” shares Dr Darren Budd, Managing Director, BASF plc. “Partnering with leading universities such as Imperial, UCL and Aberystwyth allows us to bring together brilliant minds but most importantly align research with real-world processes and requirements from the start. These kinds of collaborations are crucial for bridging the gap between the discovery and the deployment of new technologies.”

The three universities involved in the training programme each bring complementary expertise in engineering biology and have a history of collaboration in this field.

Imperial has significant capabilities in engineering biology and AI, focusing on alternative food products at the UKRI Microbial Food Hub and the Bezos Centre for Sustainable Protein. This centre spans seven academic departments and aims to advance research in precision fermentation, cultivated meat, bioprocessing and automation, nutrition, and AI and machine learning.

The UCL Department of Biochemical Engineering contributes expertise in process engineering crucial for the industrial application of fermentation and bioconversion technologies, specifically at the Manufacturing Futures Lab at UCL East.

Additionally, the Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences at Aberystwyth will focus on technical training and equality, diversity, and inclusion, while developing student expertise in biotechnology scale-up in its pilot-scale biorefinery, which is co-located with Aberinnovation, a BBSRC-supported innovation hub.

The programme targets graduates from diverse backgrounds, including life sciences, chemistry, food science, AI, data science, business, and regulation. “We want our cohorts to have diverse expertise, for peer learning, and we have different types of supervisors who can take on these students and guide their projects, ideally in a highly collaborative fashion,” Dr Billerbeck explains.

PhD projects will be jointly developed by leading industry partners and the participating universities, with expectations that more companies will contribute to co-create and co-fund projects. Students may also propose their own projects.

Graduates of the programme will be well-positioned to enter industries where there is a pressing need for individuals with engineering biology and scale-up skills. “We currently don’t produce graduates who can immediately step into key roles in a company like BASF, for example, to take on critical scale-up projects,” notes Dr Billerbeck.

Entrepreneurship and startups present another potential career path. “Many startups are good at reaching technology readiness levels of four or five, where they can produce something at 10 litres,” Dr Billerbeck adds. “But when they need to move forward and produce more in order to be economically viable, there is also a skills or knowledge gap about how to approach this scaling.”

Other career options include working in regulation, particularly relevant for biomanufactured food products, or pursuing further academic or educational opportunities.

The training programme will begin its recruitment in December, aiming to offer a total of 28 PhDs over the next three years, with the potential for increased numbers as additional industrial partners join to co-create and co-fund projects.