Biomanufacturing Scale Up

Bioeconomy Policy

Ai Digital Biology

Bio Design

Chemicals Materials

The Bioelectric Tech Stack

Why has China produced a growing number of profitable biomanufacturing firms, while the West has accumulated stalled pilots and failed scale-ups - despite comparable scientific capability?

Over the past few years, I’ve heard more open discussion about how hard it is to scale biology. At the same time, “biotech” has become a broad label covering a wide range of technologies and capabilities. It increasingly seems useful to think of it less as a single sector and more as a set of enabling industrial technologies, each with different constraints. This piece is a first attempt to explore that framing.

What has made this framing feel increasingly necessary is not just that outcomes differ, but that they differ systematically. Similar biological capabilities seem to be producing very different industrial results, not because of differences in scientific sophistication, but because of how biological systems are embedded (or not embedded) in physical infrastructure.

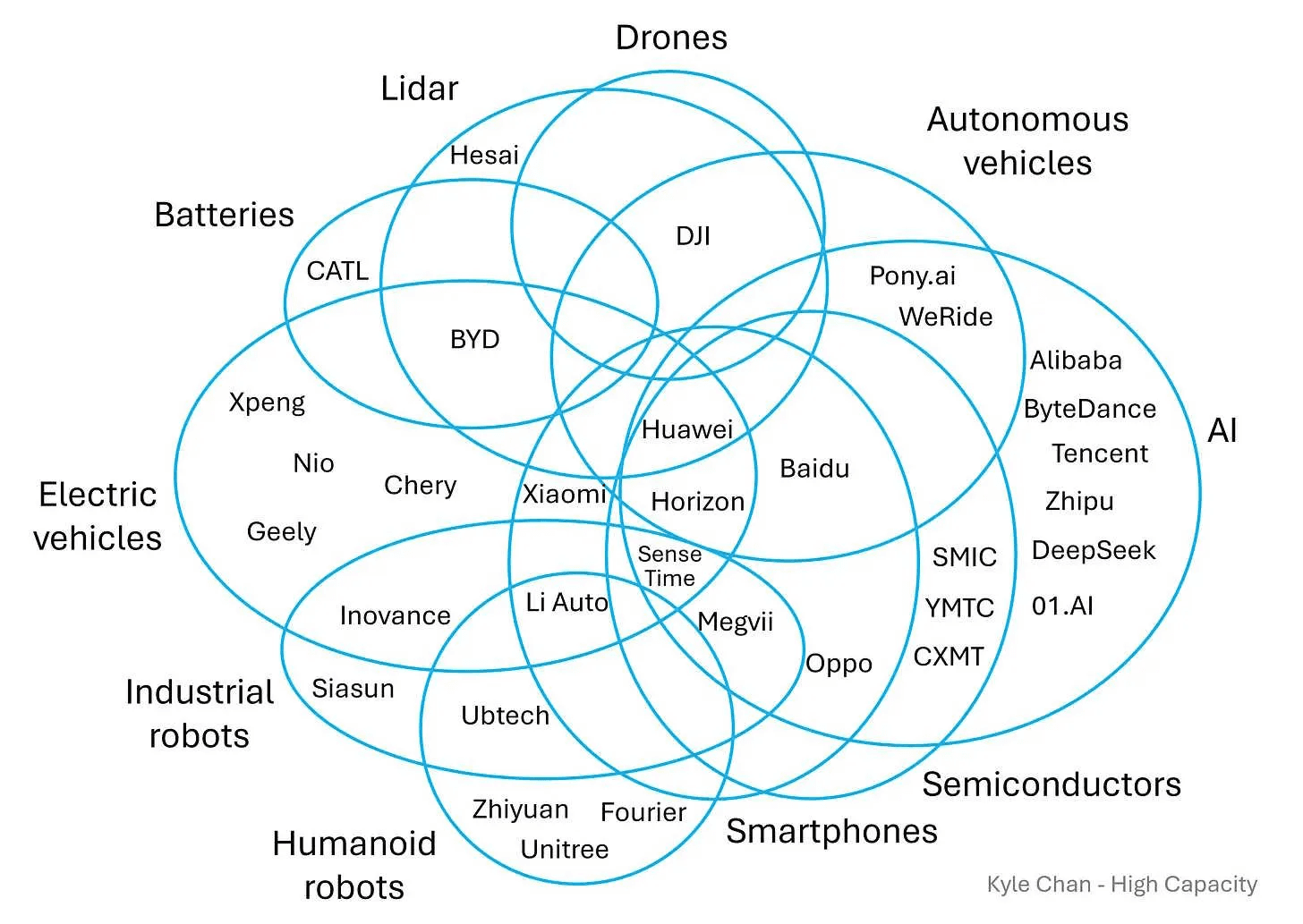

A few weeks ago, while on a robotics trade mission across China, a city government was pitching its manufacturing base to international robotics companies. What stood out was not just existing capacity, but how readily legacy industrial infrastructure could be repurposed across radically different robotics applications.

This was the result of long-term mastery of what commentators increasingly call the electric tech stack: the emerging industrial paradigm built around electricity, power electronics, motors, sensors, and control systems. Chinese firms have developed depth across this stack, a pattern clearly visible in how major players span multiple layers.

What matters is how transferable this stack has become. That transferability is not accidental; it is the result of sustained investment in physical layers that make new applications legible, affordable, and repeatable; a pattern that increasingly distinguishes Chinese industrial systems from Western ones. Once in place, it can be applied to almost any physical system. A classic example of this was XiaoMi expanding from making smartphones to electric cars.

Biology, I would argue, is about to occupy a similar position, but in a very different part of the system.

Why Biology Is Becoming the Chemical Layer of the Electric Economy

Over the last decade, technology discourse has been dominated by software, and more recently by AI. In parallel, a clearer mental model of the electric tech stack has emerged: electricity generation, power electronics, motors, sensors, and control systems that allow software to act on the physical world.

What this framing misses is a basic industrial reality: AI can design almost anything, but it cannot manufacture complex matter on its own.

In the fossil-fuel economy, that translation layer was petrochemicals. Oil was refined into molecular intermediates that became fuels, plastics, materials, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods at scale.

In an electrified economy, hydrocarbons increasingly cannot play that role.

There are several reasons for this: petrochemical supply chains are geopolitically fragile, increasingly constrained by sustainability pressures, and petrochemistry itself is poorly suited to producing the kinds of complex, highly functional molecules the next phase of industrial development will demand.

Biology offers an alternative.

Biological systems are complex matter transducers. They take relatively simple, low-value inputs (CO₂, sugars, amino acids) and convert them into highly structured, high-value molecules at scale, with electricity ultimately upstream, even when expressed through chemical inputs. In principle, biology can produce molecular structures beyond the reach of petrochemistry, provided the surrounding systems support it.

Biotechnology, then, is not just another vertical of the electric economy. It is becoming its chemical manufacturing layer.

This framing helps explain why biotech has produced many impressive demonstrations, but relatively few robust industrial outcomes. At experimental scale, biology often resembles software: iteration is fast, experiments are cheap, and failure carries limited penalties. At industrial scale, this resemblance disappears. Biomanufacturing becomes the continuous conversion of electricity and feedstocks into molecules under tight physical constraints, where energy, mass transfer, sterility, uptime, and reliability dominate outcomes. Whether this transition succeeds in practice depends less on biological novelty than on whether ecosystems treat biology as industrial infrastructure or as an extension of research, a distinction that is increasingly visible between China and the West.

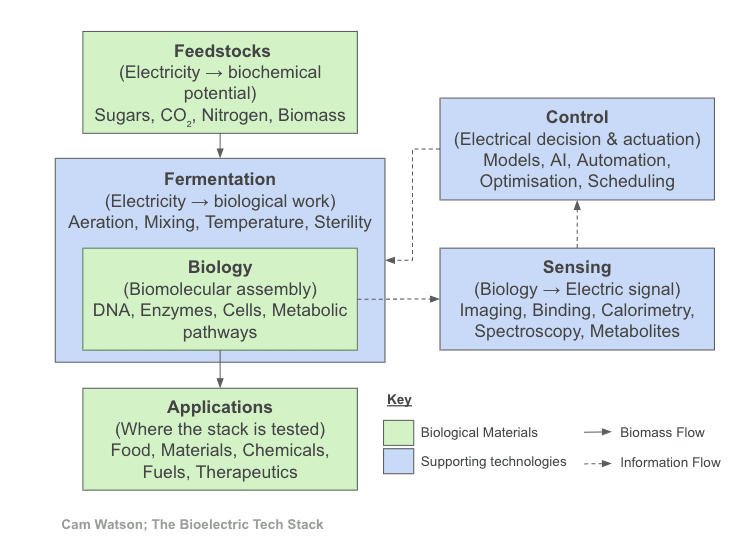

The Bioelectric Stack Is Defined by Touch Points, Not Tools

Rather than thinking about specific technologies, it is more useful to map the specific touch points where electricity meets biology. These touch points are also where different ecosystems diverge most sharply: not in the tools they possess, but in which interfaces they stabilise early and which they leave fragmented or implicit.

Feedstocks: Turning Electricity into Biomass

Biomanufacturing is often framed as a strain-engineering or reactor-design challenge. At scale, it is primarily an energy problem with chemical and electrical energy being the dominant cost drivers.

At the base of the bioelectric stack sit feedstocks: the systems that convert electricity into chemically stored biological potential. In practice, this means fixing carbon, nitrogen, and other elements into reduced, biologically accessible forms such as sugars, amino acids, lipids, and biomass.

At its foundation, this is farming in a broad sense. Photosynthesis converts energy into sugars. Fertiliser production fixes nitrogen using electricity. Controlled-environment agriculture uses electricity to regulate light, temperature, water, and nutrients. All of these approaches ultimately depend on access to reliable, low-cost electricity and grid infrastructure.

Despite their technical diversity, these systems converge on similar constraints at scale. Feedstock production is capital-intensive, volume-driven, and optimised over long time horizons. Margins are thin, logistics matter, and proximity to downstream users becomes critical once transport and storage costs are accounted for. As a result, feedstocks often behave economically like agriculture, even when they are technologically sophisticated.

This creates a structural tension for the bioeconomy. Biomanufacturing demands the cheapest possible inputs, yet those same inputs are usually pulled first by food and agriculture, where demand is continuous and scale is immediate. In practice, feedstock systems are often built for food markets and later adapted for biomanufacturing, or deliberately supported to unlock higher-value downstream applications. We see this playing out in different regions: Europe emphasises flexibility between food and non-food biomass uses; China increasingly seeks to decouple industrial feedstocks from food systems altogether. Either way, feedstocks are not neutral inputs; they are a strategic layer that determines what can scale.

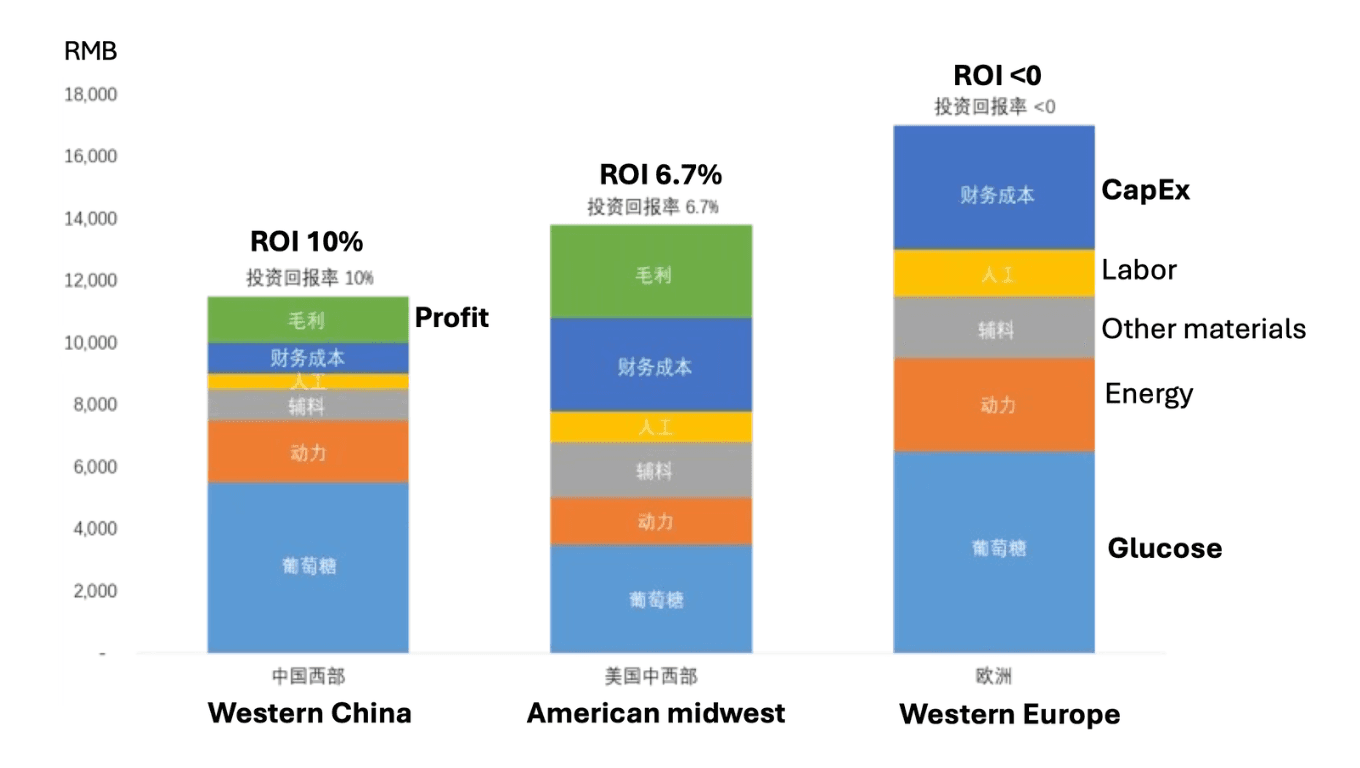

The figure below uses amino acid production as a case example to show how feedstock, energy, labour, and capital costs stack up across regions. What stands out is the dominance of glucose and energy in determining whether the system produces profit or loss.

Regional biomanufacturing cost structures (amino acids). Profitability emerges or disappears primarily through feedstock and energy costs, not biological efficiency (from Cathay Biotech's Xiucai Liu; annotated by Jinbei Li)

Fermentation: Turning Electricity into Biological Work

Once feedstock costs are locked in, fermentation inherits a hard ceiling. Yield improvements matter, but they operate within an energy-dominated cost structure that cannot be engineered away downstream.

Many approaches that perform well at bench or pilot do not fail outright at scale, but encounter a shift in constraints as energy, heat, and mass transfer begin to dominate cost. Even dramatic improvements in yield or titre eventually hit energy limits. This is why claims of step-change efficiency (fundamentally different architectures rather than incremental tweaks) are so compelling.

As a result, fermentation innovations diffuse slowly. Adoption is constrained by switching costs, long qualification cycles, and the fact that benefits often materialise downstream rather than at the point of process innovation.

For fermentation systems to operate viably at scale, demanding conditions apply: smooth scaling from prototype to industrial volumes, deep energy efficiency, modular deployment, and tight integration with sensing and automation. Fermentation energy efficiency sets the cost ceiling for the bioeconomy, constraining everything above it.

This difference shows up clearly in infrastructure investment. In the West, fermentation capacity is often concentrated in a small number of shared facilities, with initiatives such as BioMADE attempting to rebuild lost capability. China has prioritised the build-out of fermentation capacity and manufacturing infrastructure, treating bioproduction capacity itself as strategic. The result appears to be earlier confrontation with energy, cost and reliability constraints as well as faster convergence on what can actually scale.

The Biology Layer: From Low- to High-Order Biomolecular Complexity

At the centre of the bioelectric tech stack sits biology itself.

Over the last few decades, biological systems have become increasingly engineerable: DNA can be synthesised at scale, microbial strains and enzymes can be designed with specific functions, and some reactions can now be run outside living cells using cell-free systems.

We start with simple inputs (sugars, amino acids, carbon dioxide, nitrogen) that are abundant, cheap, and chemically uncomplicated.

These inputs are placed inside a biological process (cells, enzyme cascades, or cell-free systems) that assembles them into far more structured forms. Using energy, biology arranges atoms into precise configurations: chains, folded structures, and functional active sites.

The output of this process is high-order molecular complexity: proteins, polymers, fine chemicals, advanced materials, or therapeutic compounds. These molecules are valuable not because of what they are made of, but because of how precisely they are arranged.

Biology is valuable not because it ‘makes things grow,’ but because it can reliably build molecular structure at scale. It is a manufacturing system for certain classes of molecular complexity.

A strategic move in China has been to commoditise biology as fast as possible by turning strains, enzymes and nucleotides into standardised industrial inputs rather than bespoke research artefacts. In the West, much of that capability remains tied to exploratory workflows. At scale, the difference determines whether biology compounds as infrastructure or stalls as craft.

The Sensing Layer: Biology to Electric Signal

Sensing is how biology becomes legible to machines.

Beyond a handful of universal measurements (molecular binding being the most prominent) biology resists standardisation. Meaningful insight becomes organism- and process-specific. As a result, sensing fragments into bespoke systems and services.

This makes sensing difficult to standardise or generalise, even though without it closed-loop control is impossible and scale-up becomes guesswork. Many biotech failures attributed to ‘execution’ often trace back to inadequate sensing, where incomplete observability obscures what is happening inside the system.

Most innovation today focuses on binding and toxicity, largely because biopharma concentrates so much value there. Outside that Pareto peak lies a near-infinite long tail: metabolism, stress, pathway flux, emergent behaviour - all increasingly important as AI generates hypotheses faster than biology can validate them.

A major advance would be a more general bioelectric sensing interface capable of translating biological state directly into electrical signals. Digital microfluidics and integrated analytical platforms hint at this direction, but the space remains open. Another promising direction is adaptive on-demand protein probes that can be evolved or redesigned mid-experiment to target specific states or molecules. Finally, non-destructive internal imaging technologies (e.g. with quantum biology) suggest a future where internal cellular processes can be observed without breaking the cell itself.

Despite its centrality to scale and coordination, bioelectric sensing remains surprisingly underdeveloped. I have seen little evidence of general-purpose interfaces capable of making biological systems broadly legible in real time. Unlike other layers of the stack, sensing is not gated by industrial build-out, leaving it as a rare blue-ocean layer in biotechnology; one where genuine breakthroughs could reshape the entire system rather than a single application.

The Control Layer: Electricity That Thinks and Acts

AI and automation play three distinct and non-substitutable roles in the bioelectric stack.

Design: Exploring Biological Possibility Space

Design is the most visible role for AI. Biology is multifactorial, noisy, and non-linear, and even small systems exhibit combinatorial complexity that overwhelms human intuition. AI excels at navigating large design spaces, identifying patterns in noisy data, and accelerating Design–Build–Test–Learn loops.

But design is only the first bottleneck.

AI can generate hypotheses and constructs far faster than biological systems can physically realise them. Without reliable inputs, energy-efficient fermentation, and adequate sensing, design output accumulates rather than translating into products.

This mismatch helps explain why AI-led progress often concentrates in applications like pharma, where small volumes and bespoke processes tolerate inefficiency.

Scale-Up: Managing Non-Linearity, Not Optimising Curves

The second role for AI is in scale-up, and this is both less visible and more difficult.

Biological systems do not scale smoothly. Moving from microlitres to thousands of litres often requires redesigning process conditions and sometimes the biology itself, as effects invisible at small scale begin to dominate and failure modes shift.

In principle, this is an excellent domain for AI, but only once sufficient data, sensing, and physical realism exist. Without those foundations, AI models overfit to laboratory artefacts and fail precisely where they are most needed.

AI does not eliminate the difficulty of scale-up; it formalises and compresses hard-won operational knowledge once the system is instrumented well enough to support it.

Coordination: Governing a System That Resists Standardisation

The third role is coordination.

Biology will likely always resist full standardisation. It is context-dependent, sensitive to history, and prone to emergent behaviour. At the same time, the bioelectric economy demands far higher throughput: more experiments, faster iteration, continuous operation, and tighter integration between research and manufacturing.

This creates a coordination problem that exceeds human bandwidth. Many coordination failures originate upstream in gaps in sensing and observability rather than in decision-making itself.

One long-term role for AI is to govern complex biological operations in real time: coordinating experimental workflows, robotic labs, fermentation systems, supply chains, and manufacturing assets under uncertainty.

Here, AI and automation become inseparable: intelligence without actuation is inert, and automation without intelligence is brittle. Whether coordination succeeds or fails ultimately becomes visible when the system is asked to produce real applications.

This helps explain regional differences in outcome. Western ecosystems continue to produce some of the most capable AI models and optimisation techniques, often delivering impressive advances in design. In many cases, however, these virtual control layers have matured faster than the physical systems they are meant to govern, leaving execution bottlenecked by incomplete infrastructure.

In contrast, China’s earlier investment in instrumented physical systems means that control is applied to processes already operating continuously at scale, accelerating translation from insight to output.

The difference is not model capability, but sequencing: the Control Layer compounds when intelligence is anchored to systems that can absorb, execute, and stabilise decisions in the real world.

The Applications Layer: Where the Stack Is Tested

Everything discussed exists to enable applications. This is what most people instinctively think of as “biotech,” and where the bioelectric stack is validated or exposed.

Across food, materials, chemicals, fuels, climate technologies, diagnostics, and therapeutics, the common requirement is the same: complex molecules produced at scale. What differs is how forgiving each domain is.

Pharma and diagnostics are relatively tolerant of bespoke processes and inefficiency because volumes are small. Most other applications (food, materials, fuels, and chemicals) are high-volume, price-sensitive, and compete directly with mature incumbents.

As a result, many promising technologies stall. The biology is often sound, but the surrounding system (feedstocks, energy efficiency, sensing, and scale-up) is not strong enough to support the application.

From this perspective, applications are not just endpoints; they reveal the strengths and weaknesses of the stack beneath them. When the stack is weak, applications retreat into niches. When it is strong, they scale. XiaoMi--like agility becomes possible. The difference is not ambition or ingenuity, but infrastructure. Applications do not fail in isolation; they fail when the stack beneath them is not yet strong enough to carry them.

How the Stack Fits Together

Taken together, the bioelectric stack can be understood as a regulated process flow. Inputs supply matter and energy to biology, which transforms them into applications, while sensing and control form a feedback loop that stabilises and scales the process by acting back on inputs and operating conditions.

In practice, many teams work backwards from a specific application, because early revenue and validation demand it. At system scale, however, this logic breaks down. Application-led development can produce viable products without assembling the shared inputs, sensing, and control needed for reuse across domains. Agility only emerges once those layers exist as common infrastructure rather than being rebuilt around each new application.

In this structure, AI and automation do not substitute for physical infrastructure; they amplify it. When the underlying stack is incomplete, better design increases backlog and faster automation scales inefficiency. Whether coordination succeeds or fails ultimately becomes visible at the application layer.

Seen as a system, regional divergence is largely a sequencing problem. China invested first in building and instrumenting the physical layers of the stack, making it relatively straightforward to layer control and optimisation on top. In much of the West, virtual control matured ahead of physical capacity, producing impressive design and insight but limited compounding. The difference is not innovation, but whether the stack is complete enough for coordination to translate into sustained industrial output.

What This Implies for Coordination and System Design

This framework grew out of ongoing conversations with founders, operators, investors, and policymakers trying to scale biological systems in practice. I’m continuing to explore the technologies operating at each layer of the bio-electric tech stack, alongside the capital structures that support, or constrain, them. Feedback, counter-examples, and collaboration from people working in these layers are very welcome.

Several layers of the bio-electric stack function as shared foundations rather than standalone opportunities. Improvements in feedstocks, fermentation, and sensing reduce cost and risk across many downstream applications, while operational knowledge compounds through reuse rather than clean abstraction. Software leverage remains powerful, but it amplifies whatever physical system it is applied to.

When viewed in isolation, individual layers can appear slow, constrained, or uninvestable. Viewed as a system, they are foundational. Much of biotech’s persistent gap between technical promise and industrial outcome stems not from scientific limits, but from the absence of coordination across layers with very different dynamics, time horizons, and capital requirements.

One way to frame this coordination challenge is through a Biokeiretsu-style lens: a network-level approach in which inputs, infrastructure, process intelligence, and operational expertise are treated as shared assets whose value emerges through repeated use across many applications.

From this perspective, the core constraint on biotech scale is not invention, but the coordination of physical systems across the stack.

First posted on Decoding Bio here: https://decodingbio.substack.com/p/the-bioelectric-tech-stack